In Lamprecht v Commissioner, TC Memo 2022-91 (link to case), a John Doe summons tolled the statute of limitations and allowed the IRS to assess a 20% accuracy related penalty more than 6 years after the Taxpayers’ original income tax returns were filed. The IRS was able to assess the penalty even though the Taxpayer had already amended their returns in question and paid the associated tax. The Taxpayers’ amended return did not shield the Taxpayers from the penalties because the John Doe summons was issued prior to the Taxpayers’ filing their amended return.

Amending and Expatriating Did Not Stop the IRS

The Taxpayers in Lamprecht were Swiss citizens that held U.S. Green Cards for the tax years at issue, 2006 and 2007. The Taxpayers timely filed 2006 and 2007 U.S. Form 1040s. In 2010, the Taxpayers relinquished their Green Cards after moving back to Switzerland. To mark their exit from the U.S. tax regime, the Taxpayers filed Form 8854, “Expatriation Information Statement”. The Taxpayers also timely filed their 2010 Form 1040 in April 2011.

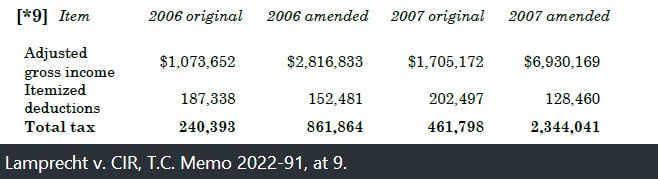

While the Taxpayers’ original 2006 and 2007 returns reported adjusted gross income of over one million dollars, the Taxpayers failed to include millions of dollars of foreign income on those returns. The foreign income originated from commissions that Taxpayer-Husband, an investment consultant, received for referring clients to the Swiss bank UBS AG (“UBS”).[1] In December of 2010, the Taxpayers filed amended returns their 2006 and 2007 returns to report the omitted foreign income. The Taxpayers did not self-report any penalties (e.g., accuracy-related penalties). The Taxpayers paid the additional tax shown on their amended returns.

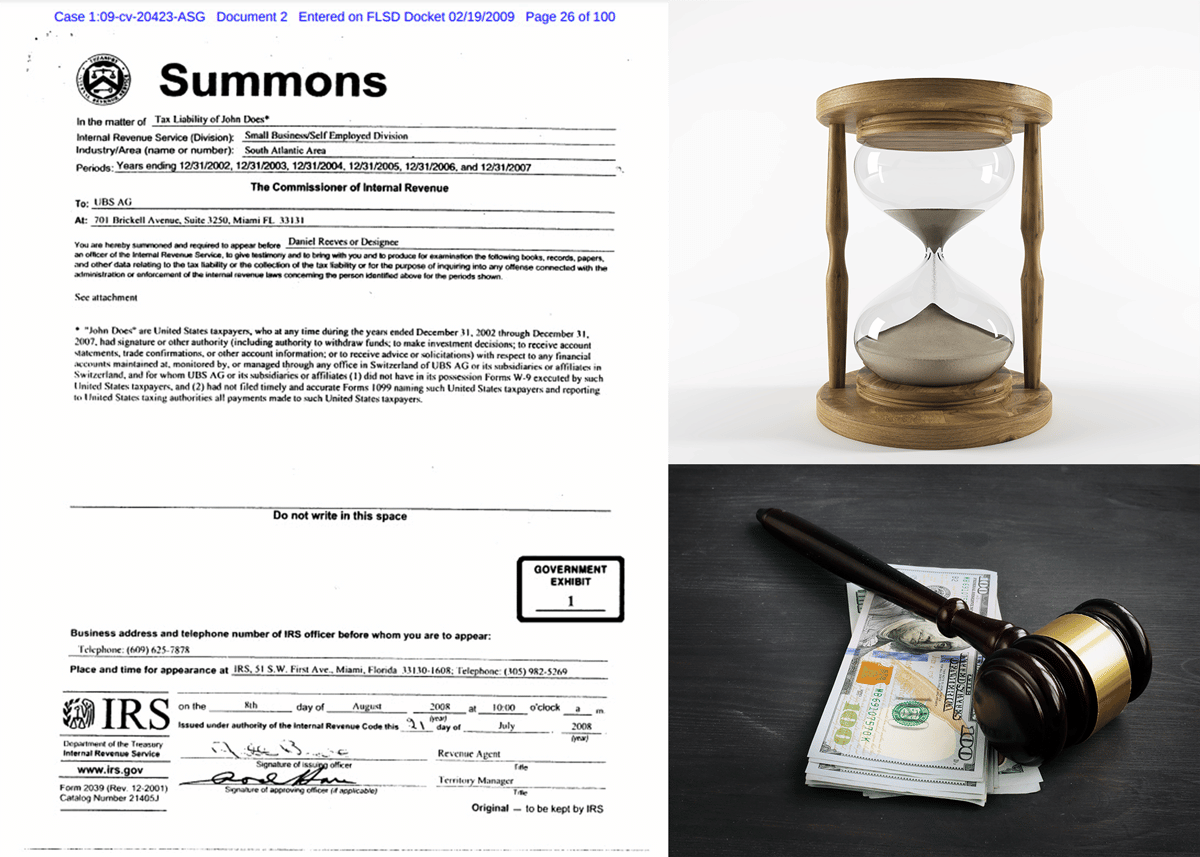

However, by the time the Taxpayers filed their amended returns, the IRS had already served a John Doe summons on UBS. In June 2008, the Department of Justice filed an ex parte petition to serve a John Doe summons on UBS. The petition was brought in federal District Court for the Southern District of Florida.

The summons sought information on U.S. taxpayers that had authority, from the beginning of 2003 until the end of 2007, over UBS accounts and for which UBS did not report account activity to the U.S. on Form 1099. In July 2008, the district court approved the petition and the IRS served UBS with the John Doe summons in July 2008. In August 2009, UBS and the DOJ stipulated to dismiss the enforcement suit because UBS agreed to cooperate. However, the IRS did not formally withdraw the summons until after UBS provided information. The formal withdrawal took place in November 2010.

UBS’s response to the summons included the Taxpayers’ account information.

In late 2013, the IRS opened an examination of the Taxpayers’ 2010 return. In February 2014, during the examination of the 2010 return, the IRS opened the Taxpayers’ 2006 and 2007 returns to assess accuracy related penalties (i.e., to assess penalties on the amount reported on the Taxpayers’ amended 2006 and 2007 returns).

In January 2015, the IRS issued a statutory notice of deficiency (“SNOD”) to the Taxpayers. The SNOD proposed to assess the accuracy related penalties of $124,294 for 2006 and $376,449 for 2007. The Taxpayers petitioned Tax Court. The IRS moved for summary judgment. The Tax Court agreed and entered judgment as a matter of law against the Taxpayers.

The Tax Court opinion grappled with several issues:

- Did the John Doe Summons toll the statute of limitations sufficiently to allow the IRS to assess the accuracy related penalties?

- Did the IRS’s John Doe Summons issued to UBS prevent the Taxpayers’ amended 2006 and 2007 returns from constituting Qualified Amended Returns, which would have prevented the imposition of accuracy related penalties?

- Did the IRS’s notice of opening 2006 and 2007 satisfy § 6751’s supervisory, written approval requirement for imposing certain penalties?

Issue 1: Did the John Doe Summons Prevent Status As Qualified Amended Returns?

Interplay of Qualified Amended Return and Accuracy Related Penalties

Taxpayers that take positions on their tax return without a “reasonable basis” or without “reasonable reliance” on a tax professional have only one way to eliminate risk of being assessed with a 20% accuracy related penalty in IRS examination before the statute of limitations expires: filing a qualified amended return.

If an amended return is considered to be a qualified amended return, then “amount shown as the tax by the taxpayer on his return includes [the] amount shown as additional tax on a qualified amended return.” Practically, this means that the additional tax self-reported on the qualified amended return is not subject to the accuracy related penalty.[2]

Therefore, if the Taxpayers’ amended return was classified as a “qualified amended return”, then the amount of tax reported on the amended returns would not be subject to a 20% accuracy related penalty. In this case, that amounts to about $500,000 for both 2006 and 2007 combined.[3]

However, not all amended returns are “qualified amended returns”. An amended return that is not considered “qualified” may still be accepted and processed by the IRS. However, it will not shield the taxpayers from accuracy-related penalties.

There are certain criteria that must be met in order to be considered a “qualified amended return.” One of the key criteria is that the taxpayer must correct the error on their original return by filing an amended return before the IRS opens an examination of the tax year and before the IRS otherwise obtains information with respect to the error or omission.

In addition, if the IRS issues a summons to a third party with respect to the error or omission before the taxpayer files an amended return, then the taxpayer’s amended return cannot be considered a qualified amended return.[4]

As a result, taxpayers are incentivized to correct their returns before the IRS begins investigating either the taxpayers’ return or the facts surrounding an error or omission on the taxpayer’s return.

John Doe Summons as Roadblock To QAR

In Lamprecht, the Taxpayers contended that 2006 and 2007 were “qualified amended returns” within Treas. Reg. § 1.664-2(c)(3).

The IRS countered that the Taxpayers’ amended returns did not qualify as “qualified amended returns” because the amended returns were filed after the IRS had served a John Doe Summons on UBS.

As mentioned above, in order to qualify as a qualified amended return, the amended return must be filed before the IRS comes to you. Specifically, with respect to John Doe summons, the amended return must be filed before:

The date on which the IRS serves a summons …relating to the tax liability of a person, group, or class that includes the taxpayer (or pass-through entity of which the taxpayer is a partner, shareholder, beneficiary, or holder of a residual interest in a REMIC) with respect to an activity for which the taxpayer claimed any tax benefit on the return directly or indirectly.[5]

The IRS issued the John Doe summons to UBS on July 21, 2008. The Taxpayers did not file their 2006 and 2007 amended returns until December 2010. The Tax Court noted that the “John Doe summons clearly ‘relat[ed] to the tax liability of a person, group, or class that includes the taxpayer’.” As a result, the Tax Court held that the John Does summons prevented the amended returns from being considered qualified amended returns.

The Taxpayers made a nuanced technical argument that amending a return to correct an omission did not disqualify an amended return from being treated as a qualified amended return. However, the Tax Court rejected this argument.[6]

Issue 2: For how long did the John Doe Summons extend the statute of limitations (i.e., were the IRS’s proposed adjustments to the Taxpayers 2006 and 2007 barred by the statute of limitations)?

The Taxpayers filed their original 2006 and 2007 returns in April of 2007 and April of 2008, respectively. The normal statute of limitations is 3 years from the date of the return. IRC § 6501(a). However, the Taxpayers and the IRS agreed that there was a substantial omission from gross income and, as a result, the statute of limitations was 6 years for the 2006 and 2007 returns.[7] Therefore, unless the statute of limitations was tolled (i.e., paused), the statute of limitations for the 2006 and 2007 returns would have been 6 years from their due date: April 15, 2013 and April 15, 2014, respectively.[8]

However, the statutory notice of deficiency was not issued until January 2015.

If there were no other facts or occurrences impacting the statute of limitations, then the statute of limitations would have closed in April 2013 and April 2014. The January 2015 issuance of the notice of deficiency would have been issued about 21 months too late.

However, the IRS raised three arguments as to why the statute of limitations was still open when it issued the notice of deficiency.

First, the IRS indicated that the fraud exception applied.[9] However, this argument was only raised and preserved for trial if necessary. The opinion did not discuss the competing taxpayer and government arguments on this issue.

Second, the IRS stated that the statute of limitations was open because the Taxpayers failed to file Form 5471, Information Return of U.S. Persons With Respect To Certain Foreign Corporations.

Under § 6501(c)(8), the statute of limitations for the entire tax return does not expire until 3 years after the date on which the IRS receives the information required under several international information reporting Code sections. However, in the event that the failure to provide the information is due to reasonable cause, then the statute is only open with respect to the items relating to such failure.

In Lamprecht, this issue was briefed, but it was not discussed for more than a few sentences in a footnote.[10] The opinion reasoned that it was a moot point because the court agreed with IRS’s third argument.

The third argument, and the one discussed at length in the opinion, was the IRS’s assertion that the John Doe summons tolled the statute of limitations for approximately 22 months.

The John Doe summons served by the IRS on UBS sought information regarding the U.S. taxpayers that, at any time during the years ended December 31, 2002 through December 31, 2007, had authority over UBS financial accounts and for which UBS did not have a Form W-9 or did not issue a Form 1099.[11] UBS’s response to the IRS included information regarding the Taxpayers’ accounts at UBS.

Under § 7609(e)(2), a John Doe summons can toll the statute of limitations if the summon is not “resolved” in six months after being served.

(2) Suspension After 6 Months of Service of Summons.—In the absence of the resolution of the summoned party’s response to the summons, the running of any period of limitations under section 6501 . . . with respect to any person with respect to whose liability the summons is issued . . . shall be suspended for the period—

(A) beginning on the date which is 6 months after the service of such summons, and

(B) ending with the final resolution of such response.

In this case, the IRS served the summons in July 2008. However, according to the IRS the summons was not “resolved” until the summons was officially withdrawn in November 2010, which was almost 28 months after being served. Per the IRS’s argument, the statute was tolled for approximately 22 months and both years would have been open.

Taxpayers Arguments Regarding the Statute Tolling

The Taxpayers raised two challenges to the IRS’s position.

First, the Taxpayers argued that the summons was not issued for a valid purpose. However, the Tax Court was not persuaded because of a lack of precedent holding either: (1) that a validly issued John Doe summons could be set aside for mixed motives; or (2) that a successful challenge to a John Doe summons precluded tolling of the statute of limitations as otherwise provided by § 7609. More generally, the Tax Court stated that the IRS’s dual motives—to use the John Doe summons as leverage over UBS to provide information and to extend the statute of limitations—was not evidence that the summons was not issued in good faith. Pursuing information from UBS via a summons and extending the statute, are both congressionally intended effects of the John Doe summons statute. Therefore, they were not evidence of bad faith even if the IRS could have obtained the evidence through an alternative means (i.e., under information sharing agreements between the U.S., Switzerland, and UBS).

Second, the Taxpayers argued that the summons was finally “resolved’ when the district court ordered dismissal of the IRS’s summons enforcement suit following entry of a stipulation of dismissal. Once the John Doe summons is “resolved” under § 7609, then the tolling period stops. This district court dismissed the enforcement lawsuit in August 2009, which was 11 months earlier than when the IRS formally withdrew the summons.

However, the court determined that the dismissal of the enforcement suit did not resolve the summons because the stipulated settlement agreement between the IRS and UBS stated that “dismissal of the suit would ‘in and of itself, have no effect on the UBS [John Doe] Summons or its enforceability’ and contemplated compliance with the summons after dismissal of the suit.” The Court reasoned that because the summons had not been fully complied with at that time, it had not been finally resolved upon dismissal of the suit. The Court pointed out that the Taxpayers did not provide another date by which UBS had “fully complied” with the summons, which may have marked the final resolution. Therefore, the Court held that the final resolution of the summons occurred on the date that the IRS formally withdrew the summons, November 15, 2010. Based upon this holding, the summons was open from July 21, 2008 to November 15, 2010.

Under § 7609, the summons tolled the statute of limitations from January 21, 2009 (6-months after the summons was served) until November 15, 2010 (the date of the final resolution of the summons). The combination of the six-year statute along with the 664 days of tolling pushed the statute of limitation out beyond the date of the statutory notice of deficiency and therefore the SNOD was issued prior to the lapse of the statute of limitations.

As a result, the IRS was not barred from asserting the accuracy related penalties for tax years 2006 and 2007.

Issue 3: Did the IRS satisfy the written supervisory approval requirement in § 6751?

The Court’s discussion on § 6751 is worthy of reading by tax practitioners, but it does not provide much instruction to taxpayers.

Numerous recent cases on § 6751 have already highlighted the statutory requirement that IRS examiners must obtain written, managerial approval of certain penalties before first officially communicating the proposed penalties to the taxpayer (i.e., the “initial determination”). Although no specific form is required, the issue hinges, in most Tax Court cases, on whether or not a penalty approval form was signed before the agent issued an examination report to the taxpayer. In Tax Court, the evidentiary issue is whether the IRS can produce the penalty approval form that was signed by the examiner’s manager demonstrating compliance with § 6751. The penalty approval form is usually signed by the manager after the examiner has already performed most of the field work for the examination.

In Lamprecht, the § 6751 analysis turned on whether or not the letter opening the 2006 and 2007 tax years for examination constituted managerial approval of the penalties. On its face, this seems to put the cart before the horse. How could the IRS manager approve the assertion of penalties for the years in question when those years had not been open for examination?

The Revenue Agent’s Managerial Request to Open a Prior Period for Examination

In Lamprecht, the Taxpayers’ filed Form 8854. “Expatriation Information Statement”, in late 2010 to report that they were no longer U.S. persons. As a result, the IRS revenue agent almost certainly was reviewing whether the Taxpayers satisfied the expatriation rules, which includes a requirement that the taxpayer must be in compliance for the year of exit and the five years before the year of expatriation. This look-back period would include 2006 and 2007.

As most tax pros can tell you, the IRS has relatively broad authority to request documents relating to the tax years under examination. If positions on prior years returns impact the year under examination, then the IRS can ask for substantiation regarding positions in those prior years even if those years are not formally under examination. In such instances, the statute of limitations may be closed for the prior year, so the request is more of a nuisance and potentially an obstacle to resolving the issue favorably for the more recent tax year under examination. This type of problem can arise in the context of basis and net operating loss carryovers.[12]

In this case, the 2006 and 2007 amended returns served as a factual basis for the penalty. They highlighted and conceded that there was an underpayment on the original return. Therefore, a quick review by the agent would have uncovered the underreporting. The IRS agent also believed that the statute of limitations was still open based upon the size of the omission on the original return and based upon the belief that the amended returns did not qualify as qualified amended returns.

Under the IRS’s internal guidelines, the agent was required to “open” the 2006 and 2007 years for examination before proposing an adjustment to them (i.e., before asserting the penalty). However, in order to open the years, the examiner needed managerial approval.

The examiner submitted an internal form (Form 5345-D), one for each year, to her manager to obtain approval to open 2006 and 2007. The form stated that the reason for opening the 2006 and 2007 returns for examination was “to assess penalties on amended return that does not meet the qualified amended return criteria”, and that the “Follow-up Actions” would be to “Open up tax year” and “Assess accuracy penalty”. The forms were signed by her manger in February 2014 and April of 2014. The examiner subsequently sent the taxpayer Letter 950, which included the examination report showing the proposed adjustments and penalties for the 2006 and 2007 tax years.

The Tax Court held that “[b]ecause the Forms 5345–D reflect initial determinations of the [Taxpayers’] liability for the section 6662 accuracy-related penalties for 2006 and 2007 and predate the first formal communication of the penalties to the [Taxpayers], the Commissioner has met his burden of production to show compliance with section 6751(b)(1).

This is further evidence that the Tax Court does not place any emphasis on the form of the approval, so long as there is an approval of the penalty and the approval is in writing.

Takeaway and Relation to other Cases

The Lamprecht case shows how filing an amended return too late can prevent penalty relief. In addition, it demonstrates how gross omissions and John Doe summons can extend the statute of limitations well beyond the normal statute of limitations.

As the IRS issues additional John Doe summons to cryptocurrency companies, the Lamprecht case provides a potential preview of challenges that lay in store for some cryptocurrency investors. Cryptocurrency investors may be blocked from limiting damage from accuracy related penalties through qualified amended returns, if the amended returns are not filed prior the IRS issuing a John Doe summons to a cryptocurrency platform through which the investor has transacted. Furthermore, the John Doe summons and a gross omission may prolong the statute of limitations for a significant period of time.

Notes

[1] Note that Taxpayer-Husband was the sole owner of a California corporation through which Taxpayer-Husband operated his investment consulting business. However, UBS deposited Taxpayer-Husband’s commissions directly into this personal UBS accounts.

[2] There is one notable exception, any amount that relates to a “fraudulent position” on the original return is not removed from the calculation of the underpayment.

[3] Accuracy related penalties are calculating by multiplying the penalty rate (generally 20%) times the “underpayment”. Generally, the underpayment equals the amount of tax required to be shown on the return less the amount shown as the tax by the taxpayer on his return.

[4] Per Treas. Reg. § 1.6664-2(c)(3), in order to be regarded as a “qualified amended return”, an amended return must be filed before the earliest of:

(A) the date the IRS first contacts a taxpayer about an examination of the return (including a criminal investigation);

(B) the date the IRS first contacts anyone regarding an abusive tax shelter, which the taxpayer claimed any tax benefit on the return;

(C) In the case of a pass-through item, the date the pass-through entity is first contacted by the IRS in connection with an examination of the return to which the pass-through item relates[4];

(D)

(1) The date on which the IRS serves a summons described in section 7609(f) relating to the tax liability of a person, group, or class that includes the taxpayer (or pass-through entity of which the taxpayer is a partner, shareholder, beneficiary, or holder of a residual interest in a REMIC) with respect to an activity for which the taxpayer claimed any tax benefit on the return directly or indirectly.

(2) The rule in paragraph (c)(3)(i)(D)(1) of this section applies to any return on which the taxpayer claimed a direct or indirect tax benefit from the type of activity that is the subject of the summons, regardless of whether the summons seeks the production of information for the taxable period covered by such return; and

(E) The date on which the Commissioner announces by revenue ruling, revenue procedure, notice, or announcement, to be published in the Internal Revenue Bulletin (see § 601.601(d)(2) of this chapter), a settlement initiative to compromise or waive penalties, in whole or in part, with respect to a listed transaction. This rule applies only to a taxpayer who participated in the listed transaction and for the taxable year(s) in which the taxpayer claimed any direct or indirect tax benefits from the listed transaction. The Commissioner may waive the requirements of this paragraph or identify a later date by which a taxpayer who participated in the listed transaction must file a qualified amended return in the published guidance announcing the listed transaction settlement initiative.

[5] Treas. Reg. § 1.6664-2(c)(3)(i)(D)(1). Note that per Treas. Reg. § 1.6664-4(f)(5), a passthrough entity includes a “partnership, S corporation (as defined in section 1361(a)(1)), estate, trust, regulated investment company (as defined in section 851(a)), real estate investment trust (as defined in section 856(a)), or real estate mortgage investment conduit (“REMIC”) (as defined in section 860D(a))”.

[6] The Taxpayers argued that they did not “claim[] a direct or indirect tax benefit from the type of activity that is the subject of the [UBS John Doe] summons.” Under the Taxpayers’ view, the omission of income was not an affirmative statement or misstatement. However, the Tax Court declined to construe the regulatory provisions so narrowly. Instead the Tax Court noted case law indicating that omitting income provides a tax benefit (i.e., reduces tax due) and alternatively that, had the Taxpayers included the omitted income, other deductions and credits would have been reduced.

[7]See IRC § 6501(e)(1)(A).

[8] Note that the Taxpayers timely filed their 2006 and 2007 federal income tax returns before April 15th. Therefore, for statute of limitations purposes, the returns were deemed filed on their due date. See IRC § 6501(b)(1).

[9] See IRC § 6501(c). The statute of limitations on a false or fraudulent return with the intent to evade tax never expires.

[10] The Taxpayers owned a corporation incorporated under the laws of the British Virgin Islands. The IRS asserted that the Taxpayers failed to provide a Form 5471 for the entity. The filing requirement for Form 5471 falls under the list of statutes under which failure to provide the required information prevents the statute from running under § 6501(c)(8). Based upon the limited information provided regarding the issue, it is not clear if there is more to the Taxpayers’ argument that the statute was not open by virtue of the failure to file Form 5471.

[11] Specifically, the summons sough information regarding “United States taxpayers, who at any time during the years ended December 31, 2002 through December 31, 2007, had signature or other authority . . . with respect to any financial accounts maintained at, monitored by, or managed through any office in Switzerland of UBS AG or its subsidiaries or affiliates and for whom UBS AG or its subsidiaries or affiliates (1) did not have in its possessions Forms W–9 executed by such United States taxpayers, and (2) had not filed timely and accurate Forms 1099 naming such United States taxpayers and reporting to United States taxing authorities all reportable payments made to such United States taxpayers.”

[12] For a discussion regarding the interplay of net operating losses, the statute of limitations, and the scope of an IRS examination, see this post: Requirements For NOL Carryforward Utilization Surviving Scrutiny in IRS Examination

Our content is reviewed by CPAs and tax attorneys with over 25 years of experience in tax law. We follow strict standards to make sure everything is accurate, clear, and up to date.

- Attorney: Justin Hughes, JD, CPA, LLM — Tax attorney and CPA; 20+ years’ experience; former Senior Manager at Deloitte M&A Transaction Services; extensive experience before the IRS, U.S. Tax Court, and state tax authorities

- Attorney: Eli Noff, JD, CPA — Tax attorney and CPA; nationally recognized in international tax compliance and enforcement defense; frequent author and speaker on IRS collections and FBAR reporting

- Recognized by: Super Lawyers, Best Lawyers, and Leading Lawyers; frequent speakers at professional associations including ABA, NATP, MSATP, and MSBA

- Focus: Civil and criminal tax matters, IRS examinations and appeals, international tax compliance, penalty abatement, and tax debt resolution

- Last updated: November 2022