FBAR Penalties and the Treasury Offset Program: Tax Court Affirms IRS’s Denial of CDP Hearing

Introduction:

In Jenner v. Commissioner, 163 T.C. 7 (Oct. 22, 2024) (link to opinion), the U.S. Tax Court held that the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) was under no obligation to provide a husband and wife with a collection due process (“CDP”) hearing prior to offsetting Social Security benefit payments under the Treasury Offset Program (TOP). The payments were to be offset against the couple’s outstanding federal debt resulting from FBAR penalties. Typically, the IRS must allow a taxpayer to request a CDP hearing before levying a taxpayer’s assets. However, the Tax Court held that the CDP hearing rights afforded in connection with a threatened IRS levy (i.e., under Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) § 6330) do not extend to FBAR penalties since they are not a “tax.”

Taxpayers’ Debt for FBAR Penalties Triggers Offsets Against Social Security Benefits Under TOP

The taxpayers were assessed FBAR penalties for failure to timely file their FBARs for 2005 through 2009. In November 2022, the Department of the Treasury’s (Treasury) Bureau of the Fiscal Service (BFS) informed the taxpayers that the TOP would offset funds (i.e., divert funds) from their monthly Social Security benefits. The BFS correspondence informed the taxpayers to contact BFS’s Debt Management Servicing Center (DMSC) to address their debts and prevent collection activity.

Within 30 days of the BFS letter, the taxpayers responded by sending the DMSC requests for CDP hearings (i.e., Forms 12153, Request for a Collection Due Process or Equivalent Hearing). In April of 2023, the taxpayers reached out to the IRS to confirm that the IRS received their CDP hearing requests.

A month later, the IRS sent the taxpayers a letter stating that they did not qualify for a CDP hearing based on the November 2022 BFS letter (i.e., the letter alerting the taxpayers that the TOP program would offset their Social Security benefits against their debts for FBAR penalties). In June 2023, the taxpayers petitioned the U.S. Tax Court, alleging that they were denied their CDP hearing rights pursuant to § 6330.

Background of TOP, IRS Levies, and FBAR Penalty Collections

Before discussing the taxpayers’ arguments and the Tax Court’s analysis, it is helpful to understand the relationship between the Secretary of the Treasury, the IRS, BFS, and Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). It is also helpful to understand each agency’s relationship to FBARs and federal taxes.

Treasury’s Bureaus and Responsibilities

The Department of the Treasury has seven bureaus[1], including the BFS, the FinCEN, and the IRS.

The IRS is responsible for carrying out the responsibilities of the Secretary of the Treasury for the administration and enforcement of Title 26 (i.e., the Internal Revenue Code).

Title 31 of the U.S. Code is entitled “Money and Finance.” It contains the Bank Secrecy Act, including code sections requiring FBARs and imposing penalties for FBAR noncompliance. FinCEN collects and analyzes this data.

The BFS is responsible for the federal government’s accounting and financing, overseeing collections and disbursements, managing the public debt, and offering shared services to enhance efficiency across federal agencies.

Assessment & Collection of FBAR Penalties

The authority to assess FBAR penalties is found in 31 U.S.C. § 5321(a)(5)(A) (“ the Secretary of the Treasury (Secretary) may impose a civil penalty on any person who fails to file the requisite form”). The Secretary of the Treasury has delegated the authority to enforce FBAR penalties to the IRS.

The authority to collect the assessed FBAR penalty remains with the Secretary, who has the authority to delegate collection “to an executive agency to take appropriate collection action.” Title 31 U.S.C. § 5321(b)(2) provides that the Secretary may commence a civil action to recover FBAR penalties. In addition, Title 31 U.S.C. § 3716 allows executive agencies to collect outstanding debts through administrative offsets.

In 1996, Congress created a centralized mechanism within the Department of the Treasury to reduce or “offset” federal payments to pay off delinquent federal non-tax debts and a variety of state debts. Federal non-tax debts include direct loans, defaulted guaranteed loans, administrative debt (e.g., salary and benefit overpayments), and unpaid fines and penalties. FBAR penalties are among the penalties that are collected under the TOP.

IRS Levy Authority and CDP Hearing Rights

Congress provided the IRS with the authority to “levy” assets under § 6331. The IRS can either issue a one-time levy (i.e., through issuing a levy notice to a bank) or it can utilize a continuous levy (e.g., wage garnishment). The IRS may execute a continuous levy through the Federal Payment Levy Program (“FPLP”).

In 2000, the FPLP was developed to integrate with the existing BFS TOP as a systemic and efficient means for the IRS to collect delinquent taxes. Whereas TOP collects a variety of federal non-tax debts, FPLP only collects delinquent federal tax debts.

Under FPLP, the IRS provides the BFS with taxpayer information necessary to establish a continuous levy on specific taxpayer accounts. Under this program, the IRS may continuously levy up to 15 percent on any “specified” payments, including Social Security benefits. Generally, before the IRS can levy a taxpayer for a federal tax debt, the IRS must provide notification of the intent to levy, which usually carries the right to request a CDP hearing before the continuous levy goes into effect.[2] However, in some instances, the IRS may institute a continuous levy before issuing a notice affording the taxpayer CDP hearing rights.[3]

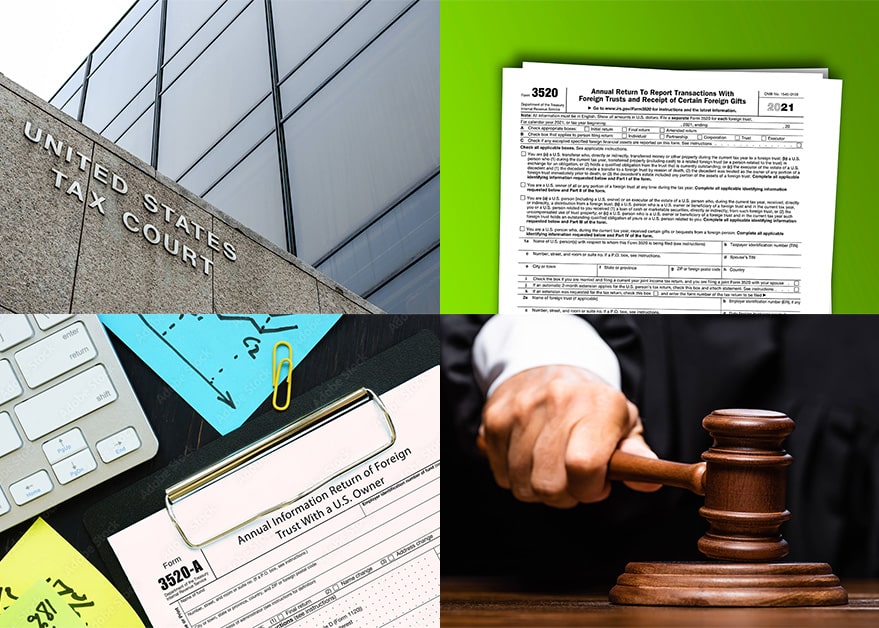

Tax Court’s Jurisdiction to Review Notice of Determinations from CDP Hearings

The Tax Court is a court of limited jurisdiction and may exercise jurisdiction only to the extent authorized by Congress. Congress granted the Tax Court jurisdiction to hear cases regarding notices of determination stemming from a CDP hearing. At the end of the CDP hearing, the IRS hearing officer issues a notice of determination. Within 30 days of a determination, the taxpayer may petition the Tax Court for review of such determination.[4]

In Jenner, the legal issue is whether the notice notifying the taxpayers that their Social Security benefits would be offset to pay their debt for FBAR penalties triggered the right to a CDP hearing and, thus, the right to petition the Tax Court for review of the determination from a CDP hearing.

Taxpayer’s Argument

The taxpayers argued that the IRS letter denying them a CDP hearing provided the requisite determination to invoke the Tax Court’s jurisdiction.[5] In short, they argued that nothing in the relevant IRC section providing jurisdiction limits the CDP hearing procedures to Title 26 liabilities. Furthermore, they argued that the administrative offsets on their Social Security benefits are “levies by the Secretary” that entitled them to a CDP hearing; and there is no “rational distinction” between levies by the Secretary to collect Title 26 liabilities and levies to collect FBAR penalties. They conclude that “the CDP procedures in IRC § 6330 apply to any type of liability . . . to the extent the Secretary files a lien or intends to levy.”[6]

Tax Court’s Analysis

The Tax Court stated that the argument was “specious”.

The court noted that it has consistently held that its CDP jurisdiction is contingent on the issuance of a valid notice of determination.[7] Furthermore, the Tax Court has held that “a taxpayer may only file a petition for review with [the U.S. Tax Court] where the administrative determination concerns a tax over which the court generally has jurisdiction.”[8]

The court notes that the CDP lien and levy code sections specifically reference “unpaid tax”.[9] However, as the court points out, FBAR penalties are not imposed by the Internal Revenue Code, and therefore, they are not “taxes.” Rather, FBAR penalties are provided for in Title 31. This distinction underscores that TOP offsets are administrative actions for non-tax debts under Title 31, separate from IRS levies under Title 26.

In addition, the court notes that “[b]ecause FBAR penalties are not imposed pursuant to Title 26, they “are not subject to the various statutory cross-references that equate ‘penalties’ with ‘taxes.’”[10] The court also explains that “nothing … provides that an FBAR penalty is deemed a tax or that it is required to be assessed or collected ‘in the same manner as a tax.’”[11]

The court notes that this leads to the conclusion that the IRS cannot use its lien or levy powers with respect to FBAR penalties. Since the IRS’s lien or levy power is not invoked, a taxpayer is not eligible for a CDP hearing based upon the Secretary of the Treasury’s collection of the FBAR penalty via offsets under the TOP.

Summary

The powers to use offsets under TOP and federal tax levies both belong to an agency within the Department of the Treasury. The Secretary of the Treasury has delegated some of its FBAR enforcement authority under Title 31 to the IRS. Nevertheless, the statutory authority for offsets under TOP and levies under the IRC are rooted in different titles of the United States Code. The IRC code sections regarding liens, levies, and CDP hearings are restricted to federal taxes and do not generally include federal non-tax debts.

“In short, Title 31 expressly provides the assessment and collection procedures for FBAR penalties, and there is no statutory, regulatory, or judicial authority providing that these penalties are subject to sections 6320 and 6330,” which afford taxpayers with CDP hearing rights.[12] As a result, taxpayers facing offsets under the TOP to pay FBAR penalties do not have the opportunity to request a CDP hearing with the IRS.

Notes

[1] The seven bureaus are Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, Bureau of Engraving & Printing, Bureau of the Fiscal Service, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Internal Revenue Service, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and U.S. Mint.

[2] See IRC § 6331(d).

[3] See generally https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/federal-payment-levy-program.

[4] IRC § 6330(d)(1).

[5] See § 6330(d)(1).

[6] See Jenner at 4.

[7] Goza v. Commissioner, 114 T.C. 176, 182 (2000).

[8] Id.; see also Lunsford v. Commissioner, 117 T.C. 159, 164 (2001).

[9] The court points to the IRC § 6201(a) to show that, under Title 26 (i.e., the IRC), the Secretary’s authority is limited to taxes (including interest, additional amounts, additions to the tax, and assessable penalties)” imposed by Title 26 (i.e., the IRC). Section 6201(a) states:

“The Secretary is authorized and required to make the inquiries, determinations, and assessments of all taxes (including interest, additional amounts, additions to the tax, and assessable penalties) imposed by this title [i.e., Title 26, the Internal Revenue Code] . . . . “

[10] See Jenner at 6 (citing Mendu v. United States, 153 Fed. Cl. 357, 365 (2021); §§ 6665(a)(2), 6671(a)). An example of penalties treated as tax are assessable penalties under Chapter 68, Subchapter B of the IRC.

[11] See Jenner at 5.

[12] See Jenner at 5.

Justin Hughes, JD, CPA, LL.M.

Justin Hughes focuses on resolving federal and state tax disputes for individuals and businesses. He has represented clients before the IRS and state taxing authorities at all stages, including audits, administrative appeals, litigation, and collections. As both an attorney and a CPA, he combines legal insight with accounting experience to help resolve tax problems for clients.