Failure to File International Information Forms Allows IRS to Assess Taxpayer More Than Five Years Past Normal Statute of Limitations

The Fairbank case demonstrates the power of IRC § 6501(c)(8) to provide the IRS the ability to assess taxpayers many years after the normal statute of limitations is closed if the taxpayer fails to file all required IRS international information reporting forms.

In Fairbank v Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2023-19, the IRS argued that, despite the fact that the taxpayers provided the information required on international information returns during an IRS examination, the statute of limitations was still open because the taxpayers did not provide the information on the actual forms. The failure to submit the forms activated a special exception to the general 3-year statute of limitations. As a result, the IRS argued that it could adjust the taxpayers’ returns even though the notice of deficiency was issued more than 5 years past the normal end date of the statute of limitations.[1]

On the other hand, the Taxpayers argued that, although they had not filed the form, they had fulfilled their statutory reporting obligation by “furnishing” the information to the IRS.

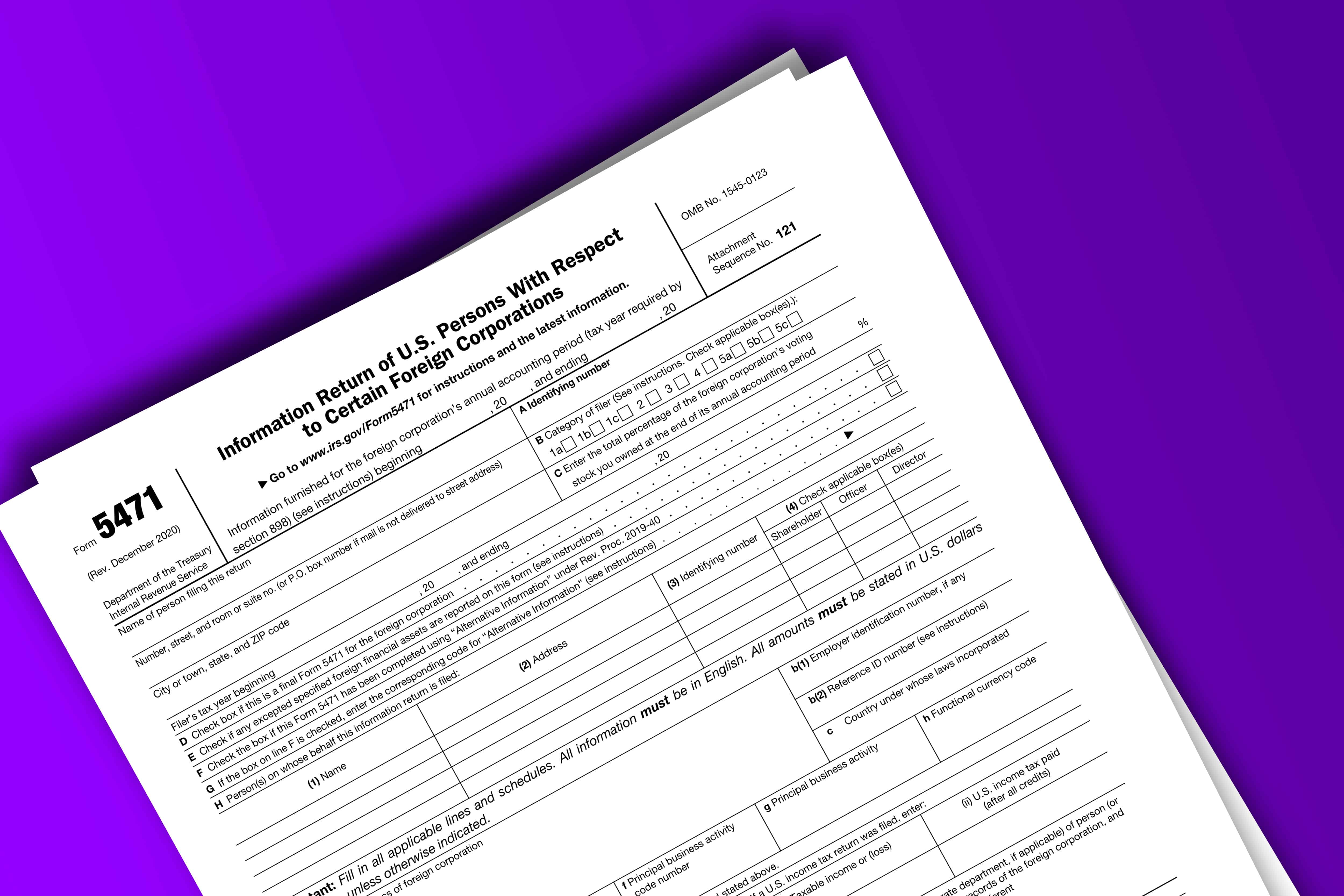

The Tax Court agreed with the IRS and upheld the IRS’s proposed adjustments to tax years 2003 through 2009 and 2011.

The case demonstrates the power of the special exception found in § 6501(c)(8) and its ability to allow the IRS to adjust a taxpayer’s return well after the normal 3-year statute of limitations. It also subtly displays difficulties that taxpayers face when they are required to carefully tip toe through an “eggshell” examination.

Brief Background

Petitioner-Wife had undisclosed foreign bank accounts, connected to a Lichtenstein establishment (Xavana Establishment) and a corporation incorporated in the British Virgin Islands (Xong Services). The foreign bank accounts were used to receive child support payments from her a husband from a prior marriage. The Petitioners failed to report income or deductions related to these accounts on their joint tax returns. The Petitioners also failed to file any international information returns regarding the foreign bank accounts and the foreign legal entities.

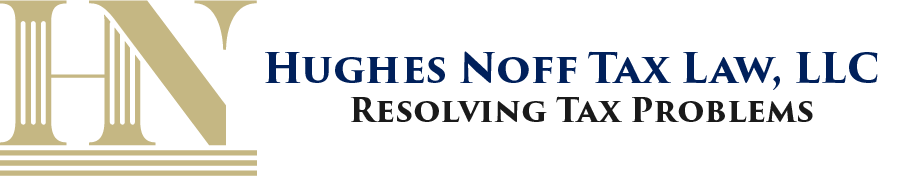

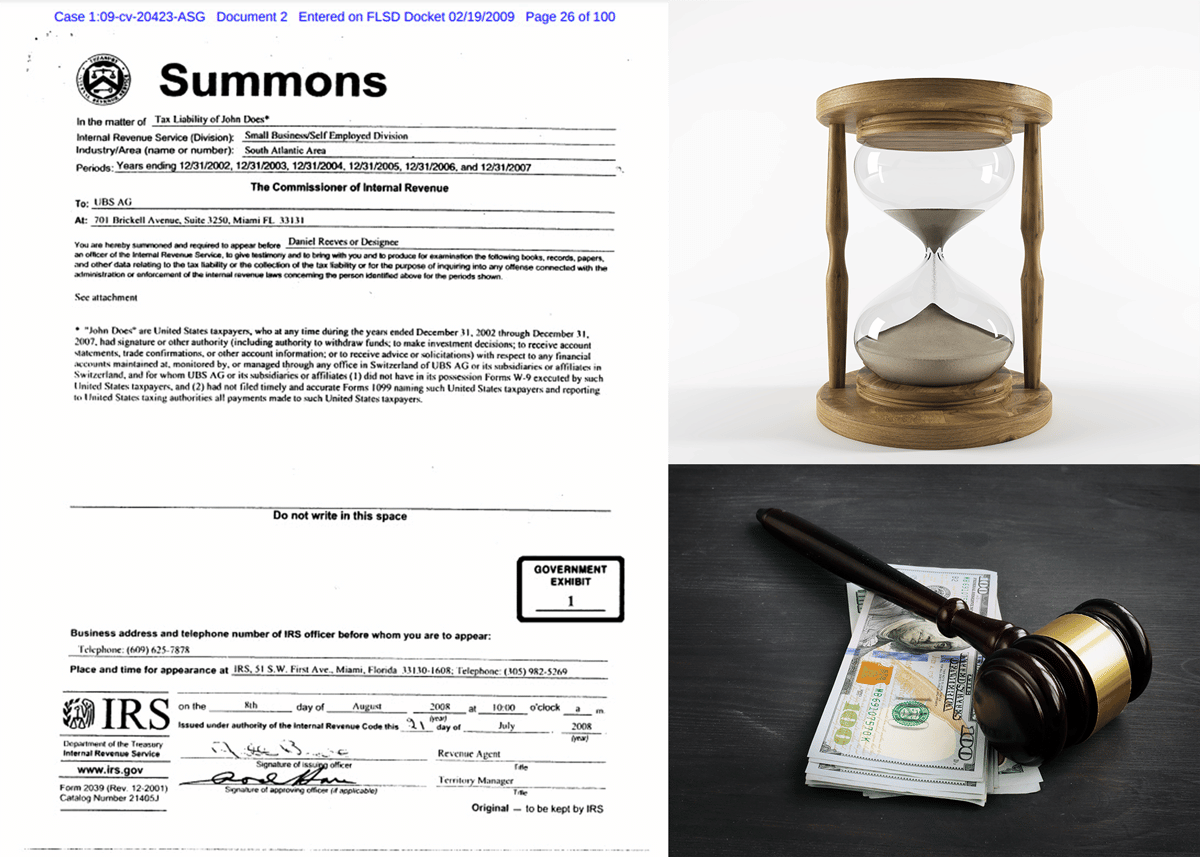

The IRS discovered the Petitioner-Wife’s UBS accounts through a “John Doe” summons issued to UBS. In 2012, the IRS initiated an examination of the Petitioners. The Petitioners were subjected to an IRS examination for tax years 2003 through 2011. During the examination, the Petitioners provided information regarding Petitioner-Wife’s bank accounts and interests in the foreign legal entities. However, the Petitioners only filed FBARs and two Forms 5471 for the BVI corporation for tax years 2010 and 2011. No other forms were filed to report the ownership or transactions with the Liechtenstein establishment.

The IRS examination culminated in the issuance of a notice of deficiency, but not until 2018, which was about 4 years after the IRS finished the field work for the examination in 2014. The proposed deficiency included tax adjustments and accuracy related penalties for tax years 2003 through 2009 and 2011.

The normal statute of limitations for the IRS to issue notice of deficiency is 3 years from the date of filing or the due date, whichever is later. See § 6501(a). The Petitioners timely filed their returns for the years in question, meaning they were filed in 2004 through 2010. The normal statute of limitations for those years would have closed in the years 2007 through 2015. So how did the IRS issue a notice of deficiency almost 5 years past the normal statute date?

The IRS determined that a special exception in § 6501(c)(8) applied keep the statute of limitations open. IRC § 6501(c)(8)(A) provided as follows:

In the case of any information which is required to be reported to the Secretary pursuant to an election under section 1295(b) or under section 1298(f), 6038, 6038A, 6038B, 6038D, 6046, 6046A, or 6048, the time for assessment of any tax imposed by this title with respect to any tax return, event, or period to which such information relates shall not expire before the date which is 3 years after the date on which the Secretary is furnished the information required to be reported under such section.[2]

The IRS concluded that the Lichtenstein establishment was a foreign grantor trust. As a foreign grantor trust, the Petitioners should have filed Forms 3520-A and Form 3520 to fulfill their reporting obligations in § 6048. However, since these forms were not filed, the IRS determined that the SOL remained open under § 6501(c)(8).[3]

The Court’s Analysis of the Lichtenstein Establishment’s Filing Obligations

Before considering the statute of limitations issue, the court first had to determine the petitioners’ reporting obligations with respect to the Lichtenstein Establishment. This led the Court to analyze three separate questions.

First, the Court had to determine how the Lichtenstein establishment was treated for federal income tax purposes under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-1 through -4. The IRS argued that it was treated as a trust[4] and the taxpayer argued that it was a business association and therefore treated as corporation. After analyzing the organizing documents and the historic activities of the trust, the Court agreed with the IRS and held that Lichtenstein establishment was a trust for federal income tax purposes.

Second, after determining that it was a trust, the Court had to determine whether the Establishment was considered a domestic trust or a foreign trust. Here the court applied the two-pronged court and control test in Treasury Regulation § 301.7701-7(a).

A trust is domestic if (1) “[a] court within the United States is able exercise primary supervision over the administration of the trust” (court test) and (2) “[o]ne or more United States persons have the authority to control all substantial decisions of the trust” (control test). Id. subpara. (1). Failure to satisfy either the court test or the control test will result in the trust’s being deemed a foreign trust for federal tax purposes. Id. subpara. (2).

The Court held that, despite that fact that the establishment had “trustees” (i.e., bank employees supervising the trust), Petitioner-Wife had sufficient control to meet the control test.[5] However, the Tax Court determined that the established flunked the Court test because there was “nothing in the record to suggest that a court within the United States was able to exercise primary supervision over the administration of Xavana Establishment”. [6] Therefore, the Court found that the trust was a foreign trust, which triggers the reporting requirements in § 6048.

Finally, once it determined that the Foundation was a foreign trust, the Court had to analyze whether the petitioner-wife was either grantor or owner of the trust under the grantor trust rules found in §§ 671-678. The Court held that although the Petitioner-Wife was not a grantor, the Court held that she had sufficient control over assets in the establishment so she was deemed to be the owner for federal income tax purposes under § 679(a) . In support of this conclusion, the Court pointed to her unilateral ability to cause distributions from the Establishment to be made to herself.

As a result, Petitioner-Wife was both an owner and beneficiary of a foreign trust, which triggers the obligation to file both Form 3520 and Form 3520-A. See § 6048(b), United States owner of foreign trust and § 6048(c), Reporting by United States beneficiaries of foreign trusts.

Tax Court says that form matters for § 6501(c)(8)

The Petitioners acknowledged that that they did not submit the actual Forms 3520 and 3520-A, but they still believed that the SOL should have run. The Petitioners argued that § 6501(c)(8) does not require a specific form and it only required that the information must be “furnished”:

shall not expire before the date which is 3 years after the date on which the Secretary is furnished the information required to be reported under such section [Emphasis added]

The Petitioners claimed that during the IRS examination, they had provided (i.e., furnished) the information required by Form 5471, Form 3520, and Form 3520A. The petitioners asserted that had they filed the forms, they would “simply be transposing the information already provided to the IRS onto an IRS form.” As a result, the Petitioner argued that since they had “furnished” the information, the SOL should have run three years after the date on which the information was furnished per § 6501(c)(8).

The IRS countered that the actual form was required to be filed in order to fulfill the requirement and start the 3-year clock on the statute of limitations under § 6501(c)(8).

The Court sided with the IRS. The Court determined that, because § 6501(c)(8) cross references § 6048, which required a “written return…setting forth a full and complete accounting of Xavana Establishment’s activities for the years at issue.” Thus, the Court reasoned that the actual form–not just the information to be provided on the form–is required to filed in order to meet the requirements of § 6048. Therefore, the Court held that the Petitioner’s had not fulfilled their statutory obligations (e.g., Petitioners never filed the Form 3520A, Form 3520, or Form 5471). [7]

In a long footnote citing Beard v. Commissioner , the Court discussed that in some instances, the U.S. Supreme Court has on some occasions held that a taxpayer has met their statutory requirements without filing the actual form and therefore the taxpayer started the statute of limitations. However, the Court notes that, even if it was possible that Beard v Commissioner could be extended to apply to § 6501(c)(8), the taxpayers did not meet the Beard test. Specifically, the “there has been no showing by petitioners that the documents furnished purport to be information returns (i.e., Forms 3520–A or 3520), that they made an honest attempt to satisfy their legal obligations under section 6048, and that the information was furnished under penalties of perjury.”

Demonstrates Difficulty of Egg Shell Examination

A commentator pointed out that, given the negative consequences of leaving the statute of limitations open, the taxpayers should have just filed the forms during the examination. However, there are two reasons why the Petitioners may not have wanted to provide the returns during the examination.

First, during the examination, the Petitioners may have believed that they had meritorious arguments[8] that they did not have to file Form 5471, Form 3520, or Form 3520A. If that was the case, then filing the forms would have started the statute of limitations under § 6501(c)(8), but it would have also foreclosed the possibility to argue that there was no filing obligation.[9]

Second, the Petitioner may have felt that there was potential criminal exposure. At the time of the examination, the IRS was investigating UBS, and the US Department of Justice had forced UBS to provide information regarding their clients.[10] There is no indication in the opinion that the Petitioners had taken part in an offshore voluntary disclosure program. Thus, the taxpayer would have been rightfully concerned that the IRS may have weighed whether or not to refer the case to IRS CI (i.e., it was an “eggshell audit”[11]). Although filing the form would not necessarily constitute an admission of criminal guilt, filing the form would have made the IRS’s task of building a case against the Petitioners easier.

Information Reporting Penalties

The Petitioner-Wife also faced undisclosed information reporting penalties for her failure to file Form 5471, Form 3520, and Form 3520A. The penalties for the forms are very high. Unfortunately, the Petitioner-Wife she did not have reasonable cause because information regarding foreign trust and foreign accounts was not provided to the petitioners’ CPA.[12]

Conclusion

The Fairbank case demonstrates the power of § 6501(c)(8) and how the failure to file a international information form can dramatically extend the statute of limitations for a tax year in which the taxpayer filed a timely tax return.

The Fairbank case underscores why it is imperative that U.S. persons (i.e., U.S. citizens, U.S. permanent residents/Green Card Holders, a those substantially present in the US) with an international financial footprint should consult with a qualified U.S. tax pro to understand their international reporting obligations. [13]

Notes

[1] Although the bar to assess the civil fraud penalty for tax purpose is very low, the opinion was silent on the fraud issue. Had the IRS successfully asserted fraud, then the statute would have remained open indefinitely, even if the petitioners had filed the forms at issue.

[2] Note that the Court’s opinion seems to have quoted a prior version of § 6501(c)(8).

[3] It is important to note that IRC § 6501(c)(8)(B) provides an exception to the exception regarding the extension of the statute of limitations. IRC § 6501(c)(8)(B) states:

(B)Application to failures due to reasonable cause

If the failure to furnish the information referred to in subparagraph (A) is due to reasonable cause and not willful neglect, subparagraph (A) shall apply only to the item or items related to such failure.

Thus, if the taxpayer has reasonable cause for their failure to file, then statute is only open with respect to the items related to the information not provided. For example, assume that a taxpayer failed to report the ownership of a foreign corporation, but they told their tax return provider about the foreign corporation and its activities. Also assume that the tax return preparer determined that a Form 5471 was not required. The taxpayer likely has reasonable cause with respect to the failure. Therefore, although § 6501(c)(8)(A) would apply to keep the statute of limitations open, the only items the IRS could adjust would be related to adjustments relating to the foreign corporation. Therefore, in this example the IRS could not adjust the taxpayer’s return for unrelated issues on Schedule A, Schedule D, etc.

[4] “The four elements of a trust for federal tax purposes are (1) a grantor, (2) a trustee that takes title to property for the purpose of protecting or conserving it, (3) property, and (4) designated beneficiaries.” Fairbank v Commissioner at 16 citing Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-4(a).

[5]The Court noted that petitioner-wife was the only individual required to make substantial decisions within the meaning of Treasury Regulation § 301.7701-7(a)(ii) . Although there were “trustees”, “[n]othing in the record suggests that any other person had the power to or attempted to veto Mrs. Fairbank’s choice in making these substantial decisions.” See Footnote 25 on page 19 of Fairbank

[6] This seems to be a murky test. Conflict of laws between the US and foreign countries are not simple. Nevertheless, the choice of law provision seemed to carry a lot of weight in the Court’s analysis.

[7] In Fairbank, the court indicates that its conclusion that § 6501(c)(8) requires the filing of the form, not just providing the information required on the form, is “consistent” with two other cases that have considered the issue: Rost v. United States, 44 F.4th 294, 298 (5th Cir. 2022); and Wilson v. United States, 6 F.4th 432, 434 (2d Cir. 2021). However, neither court was presented with the argument that providing the information satisfies the requirement that the information be “furnished”. In Rost, the Fifth Circuit concluded that § 6501(c)(8) held the statute of limitations open when the taxpayer failed to file a Form 3520 and Form 3520-A for a foreign trust, but it did not analyze the meaning for the term “furnish” and whether the actual form was necessary to start the clock in § 6501(c)(8). In Wilson, the Second Circuit did not mention § 6501(c)(8), nor did the court discuss the statute of limitations at all.

[8] The court opinion discusses some some technical arguments that Petitioners raised in defense of their failure to file. Ultimately, the Court did not agree.

[9] Although there might be a technical ability to argue later, by filing the forms, the taxpayer would have been admitting, against their interest, that the form was required to be filed. Arguing against this admission would have been difficult.

[10] For an example of another taxpayer that dealt with the UBS disclosure of clients’ information and an extension of the statute of limitations from the issuance of a John Doe Summons, see the post John Doe Summons Extended SOL & Prevented Amended Returns From Fending Off IRS Penalties here: link to post.

[11] An eggshell audit is an informal term used to describe a situation where a taxpayer is being audited by the IRS while they are aware that they have made errors or omissions in their tax returns that could potentially be considered fraudulent or criminal. “Eggshell” refers to the fact that the taxpayer and their representative must tread carefully and cautiously to avoid triggering a criminal investigation. This is difficult challenging and requires a lot of careful thought because the taxpayer and their representative need to provide the necessary information and respond to the IRS’s inquiries while minimizing the risk of exposing any potential criminal issues.

[12] Note here that the Court indicated that the petitioners’ CPA was a qualified profession for purposes of reliance. In prior cases, the IRS has asserted that a CPA credential is not enough for reliance on foreign tax issues. However, more recently, the Tax Court seems to suggest that a CPA designation is enough evidence to show sufficient expertise to justify reliance.

In Kelly v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2021-76 (link to opinion), a taxpayer failed to file Form 5471 to report an interest in a foreign corporation. The IRS pursued fraud penalties (§ 6663) and, in the alternative, accuracy related penalties. The taxpayer countered by arguing that he reasonably relied on the advice his tax return preparer. The taxpayer had timely disclosed the existence of the foreign corporation to his tax return preparer, who did not file the form. The IRS argued that, despite the act that the tax professional was a CPA, the tax professional did not have experience with Form 5471, nor did he have enough of an understanding of international information reporting to justify reliance. Nevertheless, the Tax Court held that a taxpayer reasonably relied on the advice of his tax professional regarding filing obligations for foreign corporations despite the fact that the CPA did not have prior experience with Form 5471. The Tax Court noted that the tax professional was a CPA and he had no history of adverse disciplinary actions or Internal Revenue Service (IRS) preparer penalties.

Despite the taxpayer’s victory in Kelly, taxpayers should be careful relying on a tax pro for advice regarding an issue that the tax pro disclaims knowledge or understanding of the relevant issue or topic area.

[13] For individuals that have unreported foreign financial assets, they need to understand that their options to come into compliance are limited. Filing a late foreign international information return is likely to trigger automatic information reporting penalties from the IRS. Taxpayers that receive penalty notices can appeal the penalty (i.e., by arguing reasonable cause).

Alternatively, Taxpayers may be able to utilize the streamlined disclosure programs. The streamlined programs provide the taxpayer with a structured result and mitigates the penalty exposure.

Taxpayers that are criminally willful can utilize the general voluntary disclosure program (“VDP)”. The VDP program is designed for those who have with criminal culpability (i.e., they are criminally willful with respect to their income tax reporting or payment obligations). In the VDP program, the taxpayer will still face civil fraud penalty (i.e., 75% under § 6663) for the year with the highest deficiency. The Department of Treasury does not guarantee immunity in exchange for completing a VDP. However, the Department of Treasury usually will not recommend the case for prosecution. For more see the blog post IRS Provides Updated Voluntary Disclosure Practice Guidance After Closure of OVDP here: Link

Justin Hughes, JD, CPA, LL.M.

Justin Hughes focuses on resolving federal and state tax disputes for individuals and businesses. He has represented clients before the IRS and state taxing authorities at all stages, including audits, administrative appeals, litigation, and collections. As both an attorney and a CPA, he combines legal insight with accounting experience to help resolve tax problems for clients.