Tax Court Sustains IRS’s Disallowance of C Corporation’s Deduction for Management Fee Paid to Shareholders

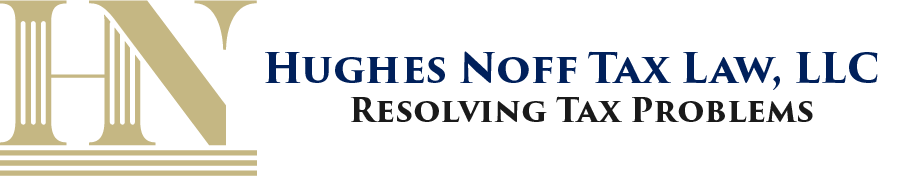

Aspro, Inc. v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 2021-8 (January 2021) is a cautionary tale for C corporations that look to zero out taxable income through post hoc management fees. In total the three shareholders received management fees in excess of a $1 million dollars a year for the years at issue (2012-2014).

Although the management fees were nominally approved by the Board of Directors at corporate meetings, the corporation did not have a structured method of computing management fees. Instead, management fees were set after the fiscal year was over. Despite the fact that the corporation had significant profits before setting management fees, the shareholders received no dividends distribution (i.e., they received no return on their equity investment).

Ultimately, the corporation could not demonstrate that the management fees were “purely for services”. Therefore, the Tax Court upheld the IRS’s determination that the management fees were non-deductible (disguised) distributions to shareholders.

In addition, the Tax Court also determined that the amounts paid to the corporate shareholders and individual shareholder were not reasonable, which was independent grounds to disallow the management fee deduction.

Burden in Tax Court For Proving Deductibility of Management Fees/Compensation

In Tax Court the Taxpayer generally bears the burden of proving entitlement to any deductions claimed.

In this case, that meant that Aspro, Inc. had to prove that the management fees were ordinary and necessary.[1] Furthermore, the taxpayer was also required to prove that the amount of each individual’s compensation was “reasonable”, which is only such an amount as would ordinarily be paid for like services by like enterprises under like circumstances.[2]

There may be included among the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred in carrying on any trade or business a reasonable allowance for salaries or other compensation for personal services actually rendered. The test of deductibility in the case of compensation payments is whether they are reasonable and are in fact payments purely for services.

Treas. Reg. § 1.162-7(a).

The Court used a facts and circumstances test (i.e., they were not bound by the labels attached in legal documents) to determine whether the payments “are in fact payment purely for services.”[3] If the Tax Court determines that the payments are distributions to shareholders disguised as compensation, then the payments are not deductible.

In the case of corporations with few shareholders, courts are wary of the increased probability that there is a lack of arms’ length bargaining between the employees and the corporation’s board of directors.

Therefore, Courts reviewing compensation closely scrutinize payments for compensation to confirm that they are not disguised distributions. [4]

Payment For Services

In analyzing the whether the “management fees paid purely for services,” the Tax Court drew negative inferences from:

- A history of no distributions to equity holders;

- management fees were roughly in proportion to the shareholders percentage interest;

- services performed by related corporations (i.e., controlled by shareholders of Aspro Inc) were not paid directly;

- the management fees were paid in lump sums after at the end of the year rather than throughout the year as services were being performed;

- there was little taxable income after the management fees were deducted; and

- the corporation lacked a structure for setting the management fees.

Dividend/Distributions:

In Aspro, “petitioner made no distributions to its three shareholders, but paid them management fees each year. Indeed, no evidence indicates that petitioner ever made distributions to its shareholders during its entire corporate history.” Aspro at 22. The Tax Court cited several cases[5] to support the determination that when there are available profits, the absences of dividends gives rise to an inference that some of the compensation really represented a distribution with respect to the corporation stock.

Management Fees Roughly Correspond to % Ownership

The management fees were not exactly pro rata among the shareholders, but they roughly corresponded to the shareholder percentage interest. The relationship between the management fees and the ownership interest was steady over the years. As a result, the Tax Court drew the inference that the shareholders were receiving disguised distributions based upon the percentage equity interest.

Services Rendered by 3rd Parties were Not Directly Compensated

In Aspro, the corporate shareholders provided services to Aspro Inc. indirectly through other legal entities. Specifically, other related corporations (controlled by Aspro’s shareholders) directed their employees to provide services to Aspro.

For example, one such employee visited the petitioner’s physical plant to provide safety advice and services. These services were not evidenced by a written contract and there were no records, invoices, or bills detailing the services provided.[6] Similarly, another employee of a related corporation also provided environmental compliance advice and services. The service was not supported by a contract or records of services rendered.[7]

The Tax Court indicated that if these services were to be compensated, then Aspro should have invoiced directly for their services by the other corporations. These services could not provide indirect support management fees claimed by Aspro’s shareholders.

Lump Sums, Tax Income and Setting Management Fees

The last several factors discussed in the opinion looked to how the fees were set, when they were paid, and the effects of their payment.

The court looked to ascertain if the fees were set in advance for services being provided. However, there was no management agreement that supported any sort of objective pricing that was bargained for among the parties. During the trial, the shareholders could not explain how the amount management fees were determined.[8] In fact, the corporation’s President and board member demonstrated that he had a fundamental misunderstanding about the nature of deductible management fees and distributions with respect to stock:

One of petitioner’s board members, [also President of Aspro], credibly testified that he understood a dividend to be a “distribution of profits”; and when he was asked to describe his understanding of the difference between a dividend and a management fee, he testified that “a management fee is a distribution from the company that’s not taxed by the company and a distribution is a [sic] after-tax distribution of profits. * * * They’re both distributions.”

Aspro at 26-27.

Furthermore, the corporation did not attempt to value the individual services attributable to the services provided by the corporation shareholder’s related entities. The individual shareholder (Mr. Dakovich) conceded that “his management fees were not paid for any specific services he performed beyond his duties as petitioner’s president.”[9]

Finally, the net effect of the deduction for management fees was little taxable income to the corporation. “Another indication that the management fees were disguised distributions to the shareholders is the fact that petitioner had relatively little taxable income after deducting the management fees.”[10]

How are each of the factors weighed? Which factor mattered most?

The Tax Court’s analysis seemed somewhat ad hoc. There was no enumerated list of factors coming from a long line of precedent. Rather, each factor/inference drawn by the court seemed to stand on its own and was not part of some larger multifactored test. However, each of the inferences were supported by prior inferences drawn in other cases. No one inference appeared to be outcome determinative. However, the combined inferences weighed heavily in favor of determining that the management fees were not purely for compensation.

Reasonableness

In addition to the ordinary and necessary prongs, IRC § 162(a)(1) and Treas. Reg. § 1.162-7(a) also require that the amount deducted be “reasonable”. The Tax Court spent time separately analyzing the services provided through the related corporations (i.e., entities related to Aspro’s corporate shareholders) and the services rendered by the individual shareholder.

Related Party Services

The Tax Court started by commenting on the lack of a written agreement and lack of invoices for services. Since there were no written management agreements or invoices, there was little written evidence of the actual services rendered in exchange for the management fee. In addition, there was no written methodology for how the fees were determined.

Reasonable compensation is only the amount that would ordinarily be paid for like services by like enterprises under like circumstances. Sec. 1.162-7(b)(3), Income Tax Regs. Petitioner presented no evidence concerning what like enterprises would pay for like services.

Aspro at 30

Unfortunately for the taxpayer, they did not provide any expert testimony to aid in assessing the reasonableness of the amounts paid for the various services. In addition, the taxpayer did not provide enough evidence of how often the employees of the related entities provided services to Aspro. [11]

We have held that management fees paid to an affiliate are only necessary and reasonable–and therefore, deductible–if the affiliate provided the management services.

Aspro at 32, citing Elick v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2013-139, at *11-*12.

The bottom line per the opinion: “Petitioner has to connect the dots between the services performed and the management fees it paid. Petitioner failed to do so.”[12]

Shareholder-Employee’s Compensation and Management Fee

In the case of Mr. Dakovich (individual shareholder and President), the Tax Court was quick to note that they were not asserting that paying a President for services was not ordinary or necessary. However, the amount paid still needed to be reasonable in relation to the services rendered.

In order to determine whether the amount paid to the Mr. Dakovich was reasonable, the Tax Court turned to a multifactored test.[13] No one factor is dispositive. In past cases, the list of factors that have been considered are:

- the employee’s qualification;

- the nature, extent, and scope of the employee’s work;

- the size and complexities of the business;

- a comparison of salaries paid with the gross income and the net income;

- the prevailing general economic conditions;

- a comparison of salaries with distributions to stockholders;

- the prevailing rates of compensation for comparable positions in comparable concerns;

- the taxpayer’s salary policy for all employees; and

- in the case of small corporations with a limited number of officers, the amount of compensation paid to the particular employee in previous years

Some Federal Circuit Courts have cast aside the mutlifactor test in favor of using the independent investor test.

The independent investor test asks whether an inactive, independent investor would have been willing to pay the amount of disputed shareholder-employee compensation considering the particular facts of each case.

Aspro at 40 citing Miller & Sons Drywall, Inc. v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2005-114, 2005 WL 1200189, at *5.

The 8th Circuit (the court to which the Aspro appeal would be heard by) has not opined on the issue. In other cases appealable to the 8th Circuit, the Tax Court has still utilized the multifactor approach, but also applied the independent investor test “as a way to view each factor.”[14]

The Tax Court found the Commissioner’s expert report[15] “helpful and persuasive.” The Tax Court spent time discussing several of factors, including (i) Employee’s Qualifications and the Nature, Extent, and Scope of Employee’s Work; (ii) General Economic Conditions for the years at issue; (iii) Prevailing Rates of Compensation for Comparable Positions in Comparable Companies; (iv) Comparison of Salary Paid with Gross Income and Net Income; and (v) Comparison of Salary to Distributions to Stockholders and Retained Earnings.

After going through each of these areas, the Tax Court determined that the President was already overcompensated by his base salary. Furthermore, there were no services rendered to the corporation beyond his responsibilities as president. Therefore, the Tax Court determined that the management fee, which was in addition to his base salary as president, was not reasonable since he was already more than adequately compensated.

Could the Taxpayer Had Done Better With Some Planning?

Unfortunately, the Tax Court’s decision was all or nothing. No deduction was allowed for the management fee because the amounts paid to each shareholder were deemed to not be purely for services and the amounts of the fees were unreasonable.

In Aspro, several of the indirect owners did appear to provide informal advice regarding project bidding and business strategy. It would not be shocking if this input helped drive some of the corporation’s ~$23million plus in gross revenues each year and the company’s million dollar plus operating margin before the management fee. However, the Tax Court indicated that the claims were too vague, and it was unclear exactly what services and how frequently the services were rendered to the corporation. In addition, it was not clear that it was ordinary for businesses in the same industry to pay for such services.[16]

Therefore, if the taxpayer was given a mulligan, it seems likely that the corporation could have paid some amounts for the services rendered by each of the parties and claimed a deduction for a management fee. The company could have created a management agreement indicating what services were to be provided by each contracting party and what rate would be paid for those services. Plus, the parties could have tracked the services rendered through timesheets or other contemporaneous documentation. However, it seems clear that such an objective, forward looking management agreement and records would not have saved the entire management fee in Aspro. Nevertheless, perhaps some portion of the management fee would have been able to withstand scrutiny.

Conclusion

The Aspro opinion shows that forethought in setting management fees and documenting services rendered in exchange for the management fee is important to sustain a deduction. Given that Aspro was a C corporation, the denial of the deduction for the three years will cost the upwards ~$1.5 million before interest.

Notes

[1] Treas. Reg. § 1.162-7.

[2] See Treas. Reg. § 1.162-7. The reasonableness test is applied on an individual-by-individual basis, not whether the total compensation on the group is reasonable.

[3] Aspro at 19 citing Sec. 1.162-7(a), Income Tax Regs..

[4] See Aspro at 20 citing Treas. Reg. § 1.162-7 and a handful of cases.

[5] Aspro at 22-23 citing Treas. Reg. § 1.162-7; Paul E. Kummer Realty Co. v. Commissioner, 511 F.2d 313, 315 (8th Cir. 1975); Nor-Cal Adjusters v. Commissioner, 503 F.2d 359, 362-363 (9th Cir. 1974) aff’g T.C. Memo. 1971-200; Charles Schneider & Co. v. Commissioner, 500 F.2d at 1.

[6] Aspro at 12-13, 31-32, and 37.

[7] Aspro at 12, 31-32, and 36.

[8] The Aspro opinion highlighted conflicting testimony from some of the board members.

[9] Aspro at 28.

[10] Aspro at 25 citing Owensby & Kritikos, Inc. v. Commissioner, 819 F.2d 1315, 1325-1326 (5th Cir. 1987)

[11] See Aspro at 33-39 discussing (i) Alternate Bid Assistance; (ii) Self Insured Plans; (iii) Human Resource Assistance; (iv) Equipment Advice; (v) Advice from Indirect Shareholder; (vi) Lobbying Activity; (vii) Investment Management: (viii) Safety Advice; (ix) Bonding; (x) Best Practices; (xi) Dredging; and (xii) Various Discounts. All of these activities appear to be items that the taxpayer claimed to have received for the payment of the management fees. These items appeared to all be provided through the relationship with Aspro’s corporate shareholder.

[12] Aspro at 33.

[13] Aspro at 39-40 citing Charles Schneider & Co. v. Commissioner, 500 F.2d at 152; Mayson Mfg. Co. v. Commissioner, 178 F.2d 115, 119 (6th Cir. 1949), rev’g a Memorandum Opinion of this Court; Home Interiors & Gifts, Inc. v. Commissioner, 73 T.C. at 1155-1156.

[14] Aspro at 40 citing Wagner Constr., Inc. v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 2001-160, 2001 WL 739234, at *22 (examining the factors from the perspective of an independent investor).

[15] The Commissioner/IRS’s expert report was put together by Ken Nunes, who is a “a chartered financial

analyst, and we recognized him as an expert in business valuation with experience in valuing compensation arrangements.” Aspro at 41.

[16] See supra Footnote 7.

Justin Hughes, JD, CPA, LL.M.

Justin Hughes focuses on resolving federal and state tax disputes for individuals and businesses. He has represented clients before the IRS and state taxing authorities at all stages, including audits, administrative appeals, litigation, and collections. As both an attorney and a CPA, he combines legal insight with accounting experience to help resolve tax problems for clients.