Easy, Partner: Becoming a Tax Partnership by Adding a New Member to a Single Member LLC

This post is a primer on the federal income tax effects of adding a new member to a limited liability company (“LLC”) that goes from a single member limited liability company (“SMLLC”) to a two member LLC. These effects include the conversion of the LLC being treated as a disregarded entity (“DRE”) to a partnership for federal income tax purposes. I will also highlight some related issues that will be discussed in subsequent posts.

Sample Fact Pattern:

Assume that in 2013 Clint contributes $35,000 in cash to a newly formed LLC to operate a small service business.[1] As a result of the contribution, the LLC only has one member (i.e., a single member LLC; SMLLC). With the contributed cash, the LLC then purchases office equipment and furniture to operate the business.

After operating for about 2 years, Clint grows the business and decides to add Duke as an equal partner. Clint and Duke agree that Duke will pay $50,000 cash for his 50% interest in the LLC. No election is made to treat the LLC as an association for federal income tax purposes.

Clint’s Formation of the LLC

Consequences of Formation

Generally speaking, an exchange of property is a taxable event that triggers gain or loss to each of the exchanging parties.[2] However, contributing the cash to the LLC in exchange for 100% of the membership interest is a non-event for Federal income tax purposes.

Why? The LLC is a disregarded entity for federal income tax purposes because it only has one member and has not elected to be taxed as an association (i.e., corporation).[3] Thus, for federal income tax purposes, there is no transfer of assets and no exchange of membership interests for assets. As a result, the basis and holding periods of the transferred assets are not affected by the transfer to a SMLLC.

In addition, the assumption of liabilities by the LLC will not cause any federal income tax consequences.[4] Why? Again, since the LLC is disregarded there is no assumption or transfer for federal income tax purposes.

Note that these rules generally work in the reverse scenario: a state law dissolution of a single-member LLC has no federal income tax consequences (assuming that no election to be taxed as a corporation has been made).

Annual Reporting

The LLC’s results of operations are reported on Schedule C, which is attached to Clint’s Form 1040. Since the LLC is disregarded, Clint does not have federal income tax basis in his membership interest.

Transfer tax note:

Even though transfers of real property might not have federal and state income tax consequences, it may trigger local tax. A transfer or retitling of property to effectuate the contribution of property or an existing business to an LLC may trigger transfer or recordation taxes. If you are transferring “real property”, you must analyze whether (a) the transfer triggers a transfer/recordation tax and (b) whether the transfer qualifies for an exception to transfer/recordation tax in your jurisdiction. This is even true when you are transferring the interests in an LLC that is holding real property.

Form Matters: Two Basic Scenarios for Adding Duke as an Equal Member[5]

In 1999, the IRS released two important partnership revenue rulings: Rev. Rul. 99-5 and Rev. Rul. 99-6. [6] Rev. Rul. 99-5 discusses the federal income tax treatment of the addition of a member to a SMLLC; and Rev. Rul. 99-6 discusses the treatment of transaction in which a two person LLC (treated as a partnership) becomes a SMLLC. The following examples are drawn from Rev. Rul. 99-5.

As Rev. Rul. 99-5 demonstrates, the legal mechanic of how a new member is added can have a significant impact on the income tax treatment. Below are the two basic scenarios:

- Duke purchases 50% of Clint’s membership interest.

- Duke contributes cash to the LLC in exchange for a 50% Interest.

For purposes of both scenarios, assume the following:

- LLC is debt free and the assets of the LLC are not subject to any indebtedness.[7]

- All of the assets held by each LLC are capital assets or property described in section 1231.[8]

- Except for their new relationship as co-members in the LLC, Clint and Duke are unrelated.

- No entity classification is made under section 301.7701-3(c) to treat the LLC as an association for federal tax purposes.

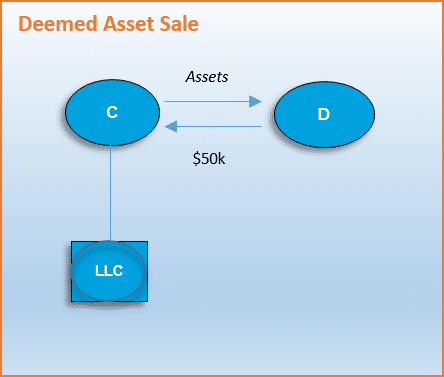

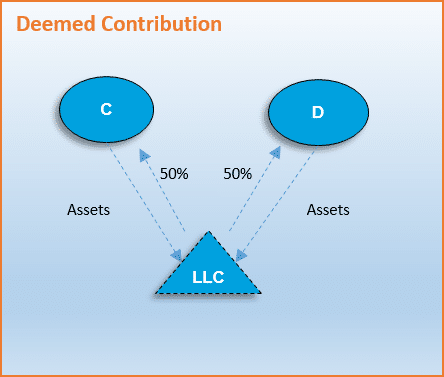

Scenario 1: Duke Purchases 50% of Clint’s Membership Interest

In Scenario 1, Duke purchases 50% of Clint’s membership interest in the limited liability company. Under the contract, Clint assigns 50% of his interest to Duke for cash. Also as part of the contract, Duke agrees to be bound by the terms of the LLC’s operating agreement, which has been amended to include Duke as a member.

As a result, Duke is now a member under state law and is subject to the organizing state’s laws on LLC’s. And, Duke is also subject to the terms and conditions of the LLC’s operating agreement.[9]

Federal Income Tax Fiction

Duke’s purchase of 50% of Clint’s membership interest in the LLC causes the LLC to have more than one member. When this happens, the LLC will be treated as a new partnership for federal income tax purposes, unless the LLC elects to be treated as a corporation or an S Corporation.[10]

For federal income tax purposes, Duke is deemed to purchase a 50% interest in each of the business assets directly from Clint. Under state law, Duke merely acquired indirect rights—through the acquired membership interest–to the business assets. However, for federal income tax purposes, Duke is deemed to receive a 50% interest in each of the assets, but just momentarily.

After the deemed asset purchase, Duke and Clint are then deemed to contribute the business assets to a partnership in exchange for an ownership interest in the partnership.

As a result of the deemed transfers, Clint recognizes gain or loss on the deemed asset sale to Duke. No additional gain or loss is triggered on the contribution to the new partnership.[11] The partnership receives a carryover basis in the assets contributed.[12] Clint and Duke have a basis in their partnership interests equal to their respective basis in the assets contributed to the partnership.[13]

Clint’s holing period in his partnership interest includes Clint’s holding period of the assets that he is deemed to contribute.[14] Duke’s holding period in his partnership interest begins the day after the purchase of his interest from Clint (i.e., the day after Duke is deemed to purchase the assets he contributed to the partnership).[15] The partnership’s holding period for the assets deemed transferred to it includes Clint’s and Duke’s holding periods for such assets.[16]

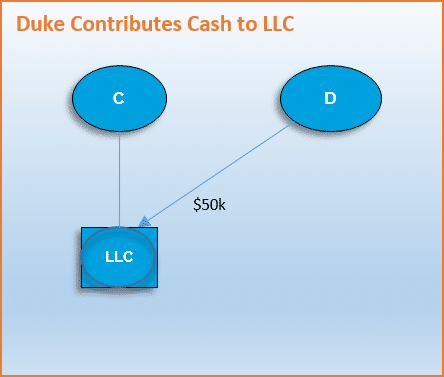

Scenario 2: Duke Contributes Cash to LLC in Exchange for Interest

In Scenario 2, Clint will take the steps required by state law to admit Duke as a new member. If Clint has an operating agreement, he will need to follow any additional requirements included in the operating agreement regarding admission of a new member.[17] In addition, Clint and Duke will want to make revisions to the operating agreement to reflect the admission of a second member.[18]

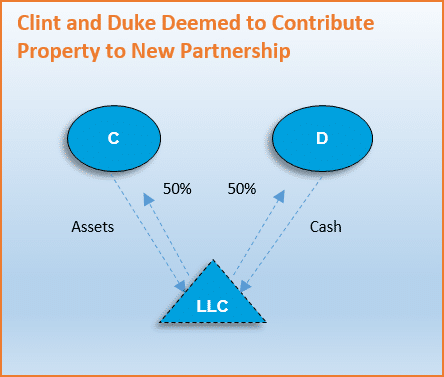

Federal Tax Fiction

In Scenario 2, the admittance of Duke as member causes the LLC to have more than one member. Under federal income tax regulations, when a LLC goes from one to two members, the DRE is converted into a new partnership.[19]

Remember, even though the business assets are held by the LLC for state law purposes, the LLC was disregarded for federal income tax purpose. As a result, Clint is deemed to contribute the business assets to the new partnership and Duke is deemed to contribute the cash.

No gain or loss is recognized as a result of the contributions. The partnership has a carryover basis in the assets contributed. Clint and Duke have a basis in their partnership interests equal to their respective basis in the assets contributed to the partnership.

Clint’s holding period in his partnership interest includes the holding period in the assets he is deemed to contribute to the partnership (i.e., when the disregarded entity converts to a partnership). Duke’s holding period begins the day after he contributes the cash to the LLC.

New Partnership Considerations

In 2015—the year the LLC converts from a DRE to a partnership—Clint reports the results of the LLC’s business operations on Schedule C for the short period prior to the conversion. Thereafter, the results of the business will be reported on Form 1065 – U.S. Return of Partnership Income.[20]

Once the partnership return is complete, both Clint and Duke will receive a federal Schedule K-1 – Partner’s Share of Income, Deductions, Credits, etc. Each partner will then report his allocable share of partnership items on his Form 1040.[21]

Summary

The major difference between the two scenarios is that Clint recognizes gain or loss in the Scenario 1, but not in Scenario 2. As a result of the deemed sale, the partnership’s holding period and basis in the assets will be differ in Scenario 1 and Scenario 2. Thus, the form of the transaction can create current tax issues that the parties should consider while structuring their transaction.[22]

This post summarizes the basic federal income tax consequences of adding a new member to a SMLLC. However there are a number of issues that were not discussed. The following section highlights some of those issues, which will be discussed subsequent posts.

Related Tax Issues:

Treatment of liabilities in Partnership Formation:

Rev. Rul. 99-5 and the examples above omit liabilities and their treatment in partnership formation. When a partnership assumes a liability the partner is relieved of an economic burden, which is treated as a deemed distribution by the partnership to the partner.[23] However, the partnership liabilities are then subject to a complex of federal income tax rules for determining each partner’s share of partnership liabilities.[24] Under these rules, to the extent a partner’s share of partnership liability is increased or decreased, the partner is deemed to make a contribution or receive a distribution of cash. The deemed contribution or distribution increases or decreases the partner’s outside basis and can trigger gain or loss.

State Tax Treatment:

Most states follow the federal tax treatment of LLCs and the “check-the-box” rules.[25] However, many states impose withholding on income that flows through to non-resident members.[26] In addition, some states impose entity level taxes on LLCs.[27]

Contribution of Appreciated Property and the application of Section 704(c)):[28]

In the examples above, Clint contributes appreciated property (i.e., property with a fair market value in excess of the adjusted tax basis in the assets. As a result, a set of complex tax rules require that the partnership track the built in gain so that the contributing partner takes into account the built-tin gain over time. These rules can alter both the economics of the partnership and the tax items flowing through to each of the partners. As a result, the partners must carefully analyze and model the interplay of the contribution of assets with built-in gain and the related terms in the partnership/operating agreement.

Allocations of Partnership Items:

The examples above presume that both Clint and Duke are 50/50 partners and provide services to the LLC. However, the allocation of partnership items–including income, losses, deductions, and credits—is very flexible.[29] This flexibility is both a pro and a con for utilizing an entity taxed as a partnership. Partnerships can accommodate many different types of economic arrangements, but drafting and applying the corresponding federal tax rules can be quite complex. In addition, to be respected for federal income tax purposes, the allocations must meet the requirements of a very complex set of rules.[30] As a result, partnership allocations can be quite complex.

Partnership Distributions:

Do not confuse allocations with distributions. Allocations generally have economic effect because a partner has an increased or decreased claim on the capital of a partnership. And, such allocations have immediate tax effect for the partners. However, this does not mean that the partners will receive any property from the partnership, which are instead distributions. As a[31]

Self-Employment Income:

Income that flows through to a general partner is generally treated as income from self-employment and is therefore subject to self-employment taxes. However, there is an exception for income flowing through to limited partners. Over the years, some taxpayers have attempted to utilize limited partnership interests (including interests in LLCs treated as partnerships for federal income tax purposes) in an attempt to exempt partnership income from self-employment taxes. Cases on the issue are divided, but the IRS has been aggressively challenging the position that active members’ income from LLC interests are not subject to self-employment taxes. See IRS CCA 201436049 (link) and Renkemeyer, Campbell, and Weaver LLP v. Commissioner, 136 T.C. 137 (2011) (link).

Guaranteed Payments:

For federal tax purposes, partners are not treated as employees of the partnership.[32] A partner is usually compensated by his allocable share of partnership income in exchange for the partner’s services provided to the partnership or the partner’s property contributed to the partnership.[33] A partner’s allocable share is generally dependent on the results of partnership operations. However, a partner sometimes receives compensation without respect to the results of the partnership operations.[34] A partner can also engage in a transaction with a partnership in a non-partner capacity. Such arrangements are subject to a complex set of rules that impact the character and timing of recognition by the partner and partnership.[35]

Partnership Interest for Services:

This example assumes that both partners contributed property in exchange for services. It is possible to exchange services for an interest in the LLC, but the exchange is not exempt from tax.[36] However, to the extent that the partner receives only a future interest in partnership profits (i.e., a “profits interest”), the recipient may have no current income inclusion.[37]

Notes:

[1] See this post (link) for a discussion of the basic steps to form a single member LLC in Maryland.

[2] Section 1001(a) provides that the gain or loss from the sale of property shall be the difference between the amount realized and the adjusted basis of the property.

[3] Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-1 and -3.

[4] Generally, if there was a “transfer” then §1001 and Treas. Reg. § 1.1001-2 would trigger gain recognition if the liabilities assumed exceeded the basis of the assets transferred to the LLC. However, on the facts of this example, any assumption by the assumption in the formation would be disregarded, even if the liabilities assumed exceeded Clint’s basis.

[5] When purchasing an interest, be careful of a potential state law distinction between membership rights and economic rights. Purchasing an economic interest does not necessarily automatically allow the purchaser to become a member.

[6] Rev. Rul. 99-5, 1999-1 C.B. 434 (Feb. 8, 1999) (link); Rev. Rul. 99-6, 1999-1 C.B. 434 (Feb. 8, 1999) (link). Rev. Rul. 99-6 has two basic scenarios: (i) one partners buys out the other partner and (ii) a third party purchases 100% of the membership interests from two equal shareholders.

[7] This is a major area of ambiguity that was not dealt with in Rev. Rul. 99-5. See comments by the AICPA (link), which will be discussed in a future post.

[8] This assumption precludes treatment of the entity as if it were an “investment company”, which could potentially change the analysis. See section 721(b).

[9] Keep in mind that there are a variety of non-tax issues to consider, but they are beyond the scope of this post. They will be discussed in a future post.

[10] See Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3; Form 8832 Entity Classification Election. The decision to elect to be treated as an association will be discussed in a future post.

[11] Section 721. Section 721(a) generally provides that no gain or loss shall be recognized to a partnership or to any of its partners in the case of a contribution of property to the partnership in exchange for an interest in the partnership.

[12] Section 723. Section 723 provides that the basis of property contributed to a partnership by a partner shall be the adjusted basis of the property to the contributing partner at the time of the contribution increased by the amount (if any) of gain recognized to the contributing partner at such time.

[13] Section 722. Section 722 provides that the basis of an interest in a partnership acquired by a contribution of property, including money, to the partnership shall be the amount of the money and the adjusted basis of the property to the contributing partner at the time of the contribution.

[14] Section 1223(1).

[15] Section 1223(1).

[16] Section 1223(2).

[17] The rules in the operating agreement may alter default rules set forth in state statutes. As a result, reading the operating agreement is critical.

[18] Going from one to more than one member raises a number of potential issues that should be considered and dealt with in a revised LLC operating agreement. For example, both Client and Duke will want to consider restrictions on the transferability of their membership interests and also whether or not they should enter into a buy-sell agreement.

[19] Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3.

[20] See Form 1065 (link) and instructions (link). The partnership return is generally due on April 15th.

[21] See example of Schedule K-1 (link) and related instructions (link).

[22] One may object to the comparison of the two examples since they are not economically identical. In Scenario 1, Clint holds Duke’s cash at the end of Scenario 1. Whereas Duke’s cash is held by the LLC at the end of Scenario 2. Nevertheless, alternative scenarios in which Clint receives cash may cause Clint to recognize taxable income anyway. The examples above still show the varying tax consequences of a sale of an interest versus a contribution directly to the LLC.

[23] Section 752 – Treatment of Certain Liabilities (link).

[24] See Treas. Reg. §§ 1.752-0 through § 1.752-7 (link).

[25] For a recent survey of state tax treatment of LLCs see this pdf (link). Maryland generally follows the federal treatment. See generally, MD Code, Tax – General, § 10-107- Application of federal income tax law (link); “Who must file” in the instructions to MD Form 510 – Pass-Through Entity Income Tax Return (link). For more information on Maryland Pass-Through Filing requirements, see this page on the MD Comptroller’s website (link).

[26] Maryland imposes a non-resident withholding tax. For more detailed information see Administrative Release No. 6, Taxation of Pass-Through Entities Having Nonresident Members (link).

[27] Maryland LLC’s are generally exempt from entity level taxes. See MD Code, Tax – General, § 10-104(8) (link). However, MD LLCs are subject to a personal property tax. See MD SDAT website for forms and instructions (link).

[29] Many partners do not provide services and are compensated solely for use of their capital. In that case, it is not uncommon for such partners to demand preferred returns on their capital. Also, some partners providing services may receive allocations based upon early results, but they may be subject to claw-backs if partnership’s performance declines.

[30] See the “substantial economic effect” rules in Treas. Reg. § 1.704-1(b)(2).

[31] When drafting the partnership agreement, the parties should consider both the ongoing capital needs of the partnership and the capital needs of the partners, especially to pay any income tax that a partner may have due to the current allocation of partnership income.

[32] A member in an LLC that is treated as either a DRE or partnership should not receive a W-2 from a partnership.

[33] Such income is reported to the partner on Schedule K-1.

[34] See generally section 707 and related regulations.

[35] Id.

[36] Only contributions of property in exchange for a partnership interest can qualify for non-recognition treatment. Section 721.

[37] See generally, Rev. Proc. 93-27 (link); Rev. Proc. 2001-43 (link); and Notice 2005-43 (link). The issuance of a profits interest is a topic of hot debate. The technique is commonly used by private equity firms and hedge funds to provide their managers compensation at capital gains rates (i.e., carried interest). See this Wikipedia summary (link).[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Justin Hughes, JD, CPA, LL.M.

Justin Hughes focuses on resolving federal and state tax disputes for individuals and businesses. He has represented clients before the IRS and state taxing authorities at all stages, including audits, administrative appeals, litigation, and collections. As both an attorney and a CPA, he combines legal insight with accounting experience to help resolve tax problems for clients.